The usefulness of support when people suspect LPA abuse

The abuse of older people or vulnerable adults is more common than people generally admit. Nevertheless, when it is witnessed or suspected, it is often unexpected, and people do not initially know what to do or where to seek help or advice.

In my own case, when we realised our father was being abused by his LPA attorney, my sister and I:

- First called the national Dementia Support Line (we were not, at that stage, aware of Hourglass and its 24/7 helpline)

- We then also called the OPG safeguarding unit.

- We then called our local adult social services team, to raise our specific concerns about his care arrangements.

- Finally, we wrote a long e-mail to the OPG safeguarding unit detailing our concerns that our father’s LPA attorney was emotionally and psychologically abusing him, and therefore breaching her duty of care as an attorney.

Ultimately, the OPG did not investigate (insufficient evidence, not considered direct abuse of the donor), and adult social services, while making a visit to the donor and attorney, were fobbed off by the LPA attorney’s lies.

What is the experience of others who witness or suspect abuse by an LPA attorney?

From where do they seek help and advice? And, do they get the help they wanted?

Similar questions were asked in a small survey of elder abuse and abuse by LPA attorneys that was circulated in 2024 and early 2025, first in response to the public response following BBC and Daily Mail coverage of the story of Vincent Stephens, and was also distributed by the office of MP Fabian Hamilton (in support of his Powers of Attorney Bill).

The survey included 48 responses from people with experience of abuse by an LPA attorney, and some of their responses have been analysed and reported in the 2nd Blog post on the nature of abuse by LPA attorneys.

In this 3rd Blog post I present and discuss the survey responses to the following questions:

- Did you attempt to get support from the authorities? and [If yes to this] Which agencies did you contact?

- and, If you did contact any agencies, please rank the support you received from each agency [i.e. in terms of its how helpful it was].

- and also, What other support did you seek?

From where do people seek support when they suspect abuse by an LPA attorney?

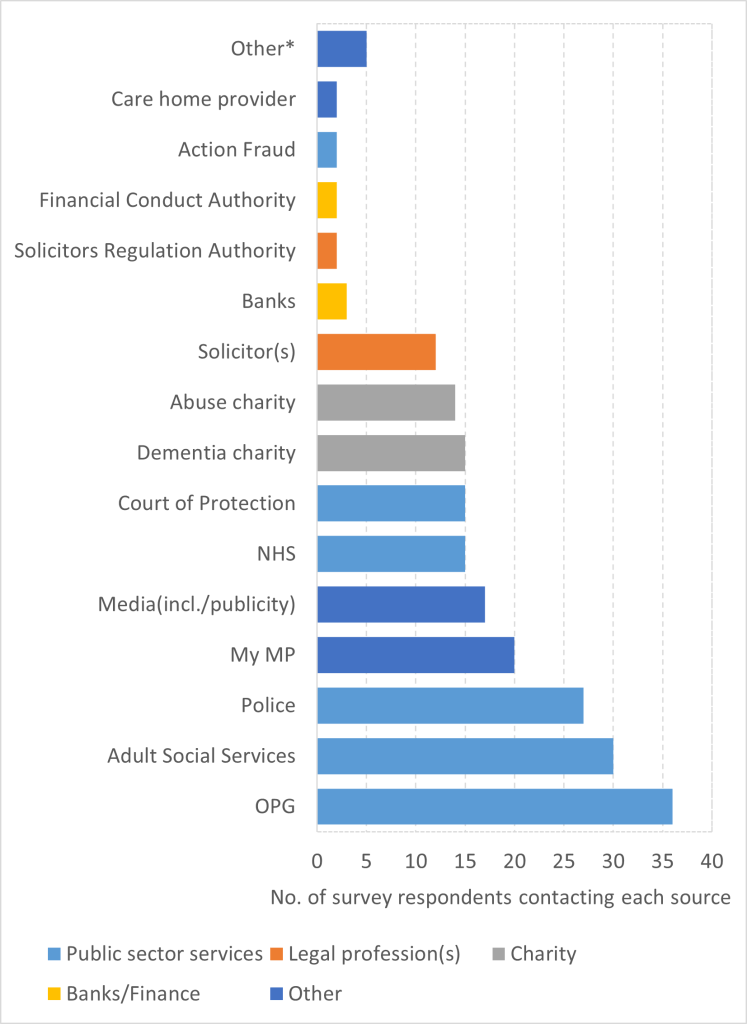

Fig.1 below shows the wide range of organisations and professionals which people turn to when they have witnessed or suspect LPA abuse. Perhaps reassuringly, around three-quarters of the 48 respondents reported their concerns to the OPG; however, this does beg the question of why the other 13 survey repondents did not share their concerns with the OPG.

* ‘Other’ category of support = Financial Ombudsman Service, Legal Ombudsman, ex-policemen, AgeSpace (charity), Therapist

After the OPG, the next most common sources where people sought help were Adult Social Services and the Police – both also having a statutory responsibility to protect people from abuse. They are also the main public services to which the OPG frequently refers people with safeguarding concerns – either because the OPG has limited jurisdiction (e.g. donor must have lost capacity for the OPG to investigate), or suggesting that these organisations have greater investigatory powers.

The next two most-sought sources of help – MPs and the Media – are concerning, because in general people only contact their MP or seek publicity via the news media when they have exhuasted and feel let down by other avenues of help. Around a third (17 and 20) of people sought support from these sources.

From this simple chart, there is an indication of the desperation and frustration that people sometimes experience with the public agencies, professionals, and financial institutions that should have the protection of older or vulnerable people at the heart of their duties and codes of practice. Even in this small sample, a number of people had resorted to contacting the ‘watchdogs’ and ‘ombudsman’ organisations that hold professions or financial institutions to account: the Solicitors Regulation Authority, Financial Conduct Authority, Financial Ombudsman Service, and the Legal Ombudsman.

On the other hand, it is reassuring that many people seem to know about, and seek help from, ‘abuse charities’ (i.e. for safer ageing) or dementia support charities (15 and 14 survey respondents respectively). But this also further underlines how people do not know where to turn for help.

How helpful are public agencies at supporting people who suspect LPA abuse?

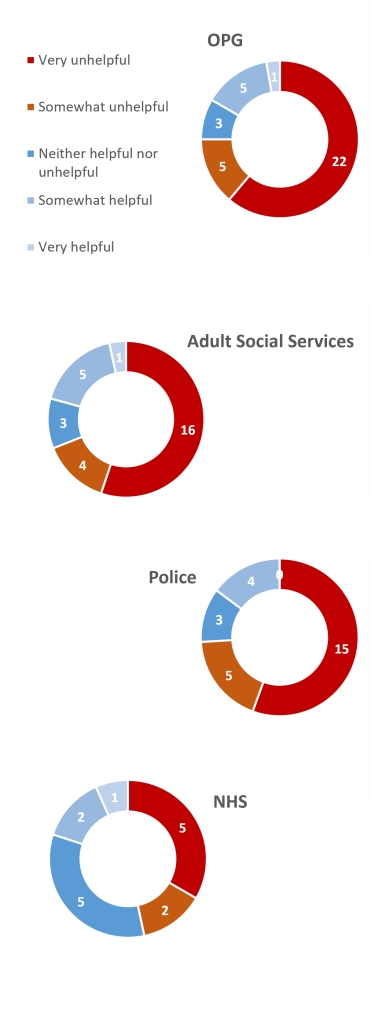

For the main public authorities that are contacted about concerns of LPA abuse, the survey asked how helpful the support received was. While again, the sample is small, the proportion of people who found the support somewhat unhelpful or very unhelpful should be alarming to these organisations. See Fig.2 below.

Three-quarters of people who contacted the OPG found the support unhelpful, of which most found it very unhelpful.

Given this is the public agency with the clearest remit to effectively deal with concerns about LPA abuse, this seems quite damning.

The proportion of people contacting either Adult Social Services or the Police who also found them unhelpful is similarly concerning – in both cases almost three-quarters of those seeking support found the support unhelpful. And for people who had contacted the NHS about suspected LPA abuse, just under half (7/15) found the support received unhelpful.

So, what does this all mean?

First, positively, a high proportion of people who suspect abuse by LPA attorneys do contact the government agency – the OPG – with the statutory reponsibility (in England and Wales) to investigate when LPA attorney’s might be breaching their duties. Increasing publicity in national TV/newspapers and media sources like Martin Lewis’s Money Saving Expert have further promoted the existence and purpose of Lasting Power of Attorney, and the role of the OPG.

That said, it is not always clear whether a suspected abuser is also the appointed LPA attorney of an alleged victim – so this may partly explain why the OPG is not contacted by some people with concerns. Interestingly, the currently tabled Powers of Attorney Bill (second reading due in June 2025) has proposed that the OPG must be responsible for better “promoting and publishing public information to ensure public awareness” of how to search the register of LPA donors and attorneys.

Another explanation of people not contacting the OPG may be when the abuse victim (LPA donor) has died; so the OPG would not be able to investigate, even if contacted.

However, even though the OPG’s responsibility to investigate has ended, there is an argument that the OPG should still collate and analyse all information about past alleged abuse by LPA attorneys, in order to develop intelligence about how attorneys perpetrate abuse and what patterns and earlier reported signs predict likely abuse of their donor.

Less positively, people with concerns about LPA abuse end up seeking help from multiple agencies, helplines and organisations. On average, the 48 people in this survey with concerns about LPA abuse, sought help from 4.5 sources (organisations or professionals). A significant minority resorted to seeking help from their MP, the news media, or various professional regulators (SRA) or ombudsman services – further underlining people’s frustration with, and lack of help received, from the frontline agencies or professionals that should care the most.

When it comes to whether people got the support they needed from those government agencies with an explicit safeguarding role (OPG, police, adult social care, NHS), this small survey showed that between two-thirds and three-quarters of people found the support received either somewhat unhelpful or very unhelpful (see Fig.2). While this is a small survey, and may have attracted more people with negative help-seeking experiences (e.g. it was promoted after BBC news stories about LPA abuse, and alongside a parliamentary campaign), this level of dissatisfaction with public agencies – often at a time of considerable distress and worry about an at-risk loved one – seems unnacceptable.

All of this strongly supports (UK) MP Fabian Hamilton‘s arguments that the OPG is not doing enough to investigate suspected abuse by LPA attorneys, and that – as his private member’s bill proposes – a review of this aspect of the OPG’s responsibility is long overdue. Specifically, the Powers of Attorney Bill proposes that a review should investigate:

- whether the existing powers of the Office of the Public Guardian are sufficient to enable it to carry out its duties,

- whether the Office of the Public Guardian is using its powers effectively to safeguard donors, and

- whether there is a need for any change to the powers of the Office of the Public Guardian.

Alongside this, it seems clear that the Police, Adult Social Services, the NHS – and solicitors and banks – need more consistent, informed and helpful approaches to sensitively and effectively handle concerns raised about suspected LPA abuse.

Leave a comment